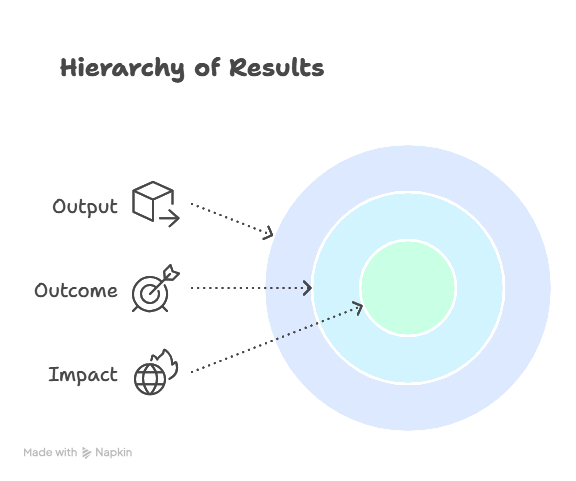

One of the most common mistakes in developing a Theory of Change is confusing outputs, outcomes, and impact.

These three elements form an interconnected chain where each builds upon the previous one, creating a logical pathway from what you do to the change you ultimately want to see in the world.

Outputs: What You Directly Produce

Definition: Outputs are the direct, tangible products of your activities—the goods, services, or deliverables that your organization produces and has complete control over.

Outputs represent the most concrete and controllable aspect of your work. They fall entirely under your direct control, meaning you can guarantee their delivery as long as you have the necessary resources and capacity.

These deliverables are inherently measurable without requiring comparison groups or complex evaluation designs, as they can be counted or quantified immediately upon completion.

Fundamentally, outputs answer the straightforward question of “What did we produce?” and serve as the foundation for all subsequent change.

Examples across sectors:

- Education: 500 teachers trained, 50 schools equipped with digital tablets

- Healthcare: 10,000 vaccines administered, 25 community health workers certified

- Environment: 1,000 solar panels installed, 200 tons of waste recycled

- Financial inclusion: 2,500 microloans disbursed, 15 financial literacy workshops conducted

Outcomes: The Changes That Result

Definition: Outcomes are the changes in knowledge, skills, behavior, or conditions that result from your outputs. Unlike outputs, you don’t have complete control over outcomes because they depend on how people respond to and use what you’ve provided.

Outcomes venture into territory that is partially beyond your control, as they depend on how beneficiaries respond to, engage with, and utilize what you’ve delivered.

This makes them significantly more challenging to guarantee and typically requires comparison groups or baseline measurements to assess effectively.

Unlike outputs, which can be measured immediately, outcomes usually need time to manifest, ranging from weeks to years depending on the nature of the change being sought.

At their core, outcomes address the crucial question of “What changed as a result?” and represent the first real evidence that your intervention is creating meaningful change.

Examples building on the outputs above:

- Education: Teachers improve classroom instruction quality, student test scores increase by 15%

- Healthcare: 80% reduction in vaccine-preventable diseases, community health knowledge improves

- Environment: Household energy costs decrease by 30%, local air quality improves

- Financial inclusion: 60% of borrowers increase their income, participants develop saving habits

Impact: The Long-Term Transformation

Definition: Impact refers to the broader, long-term changes in systems, communities, or society that result from sustained outcomes over time.

Impact represents the most ambitious and far-reaching level of change, emerging only over years or decades of sustained effort.

These transformations affect entire communities or systems rather than individual beneficiaries, creating ripple effects that extend far beyond the direct recipients of your intervention.

Impact rarely results from a single organization’s work alone but typically requires multiple interventions working together across various actors and timeframes.

This level of change addresses the fundamental question of “What fundamental change occurred?” and represents the ultimate aspiration for most social enterprises seeking to create lasting transformation.

Examples building on the outcomes above:

- Education: Regional education quality improves, economic development in the area accelerates

- Healthcare: Community health systems become self-sustaining, population health indicators improve

- Environment: Local renewable energy market develops, community becomes climate resilient

- Financial inclusion: Poverty rates decline, women’s economic empowerment increases regionally

The Interconnected Chain: How They Work Together

The power of a Theory of Change lies in understanding how these elements connect and influence each other:

1. Linear Progression

Each level builds on the previous one: Activities → Outputs → Short-term Outcomes → Long-term Outcomes → Impact

2. Feedback Loops

Outcomes can influence future outputs:

- Successful outcomes attract more funding for expanded outputs

- Poor outcomes signal need to adjust activities and outputs

- Impact creates enabling conditions for greater outputs

3. Multiple Pathways

Single outputs can contribute to multiple outcomes:

- Teacher training (output) can improve both student learning and teacher retention (multiple outcomes)

- Solar panel installation (output) can reduce energy costs AND improve air quality (multiple outcomes)

4. Cumulative Effects

Impact often requires multiple outputs and outcomes working together:

- Community health improvement requires vaccination programs AND clean water AND nutrition education

- Economic development requires financial services AND business training AND market access

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Mistake 1: Using outputs as proxy for impact

- Wrong: “We’ve achieved impact because we trained 1,000 people”

- Right: “We trained 1,000 people (output) who improved their practices (outcome) contributing to sector transformation (impact)”

Mistake 2: Claiming impact too early

- Wrong: “After 6 months, our program has impacted the community”

- Right: “After 6 months, we’re seeing promising outcomes that may contribute to long-term impact”

Mistake 3: Ignoring the connections

- Wrong: Measuring each level in isolation

- Right: Tracking how outputs lead to outcomes and contribute to impact

Practical Framework for Your Theory of Change

Use this template to map your interconnected chain:

Our Activities produce Outputs: “We will [activity] to produce [specific, measurable output]”

Our Outputs create Outcomes: “When we deliver [output], this will result in [behavioral/knowledge/condition change] because [assumption]”

Our Outcomes contribute to Impact: “As [outcome] is sustained over time, it will contribute to [systemic/long-term change] in our target population”

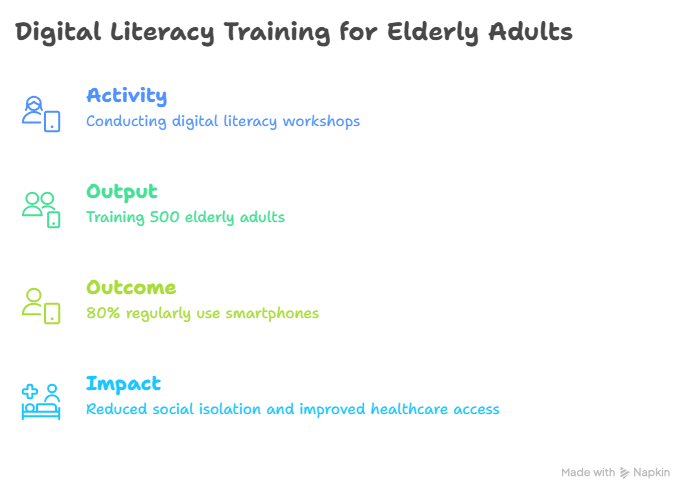

Example in practice:

- Activity → Output: We will run digital literacy workshops to train 500 elderly adults in smartphone use

- Output → Outcome: When we train 500 elderly adults, 80% will regularly use smartphones for communication because they’ll have the confidence and skills needed

- Outcome → Impact: As elderly adults become digitally connected, social isolation in our community will decrease and healthcare access will improve through telemedicine adoption

Why This Matters

Understanding these interconnections helps impact organizations and social enterprises design better interventions by thinking through the full change pathway, set realistic timelines for when to expect different types of results, communicate effectively with funders who want to understand your logic, measure appropriately by tracking the right metrics at the right time, and identify gaps where your outputs aren’t leading to expected outcomes.

Remember: Your Theory of Change should show clear, logical connections between each level.

If you can’t explain how your outputs will lead to outcomes, or how your outcomes contribute to impact, you may need to reconsider your approach or develop additional interventions to bridge the gaps.