When Maria Rodriguez took over as Executive Director of Community Learning Partners, a youth education nonprofit in Oakland, California, she inherited a well-intentioned organization with a serious problem.

No one could clearly explain how their programs actually created change.

Board members asked different questions than funders.

Staff measured different metrics than leadership wanted.

Three years of “successful” programming had produced surprisingly little evidence of lasting impact.

Sound familiar?

Maria’s challenge reflects a widespread struggle in the social sector.

Despite billions invested annually in social programs, many organizations cannot articulate—much less demonstrate—their pathway to meaningful change.

The solution often lies in choosing and implementing the right strategic planning tool.

But with so many frameworks available, how do you decide?

Two models dominate the landscape: the Theory of Change and the Logic Model.

While often used interchangeably, these frameworks serve different purposes.

They operate with distinct philosophies and produce varying results.

Understanding when and how to use each tool can mean the difference between programs that merely produce outputs and interventions that create lasting transformation.

This guide examines both frameworks through practical application.

It will help you determine which tool best serves your organization’s strategic needs.

Understanding the Theory of Change: Thinking Backward from Impact

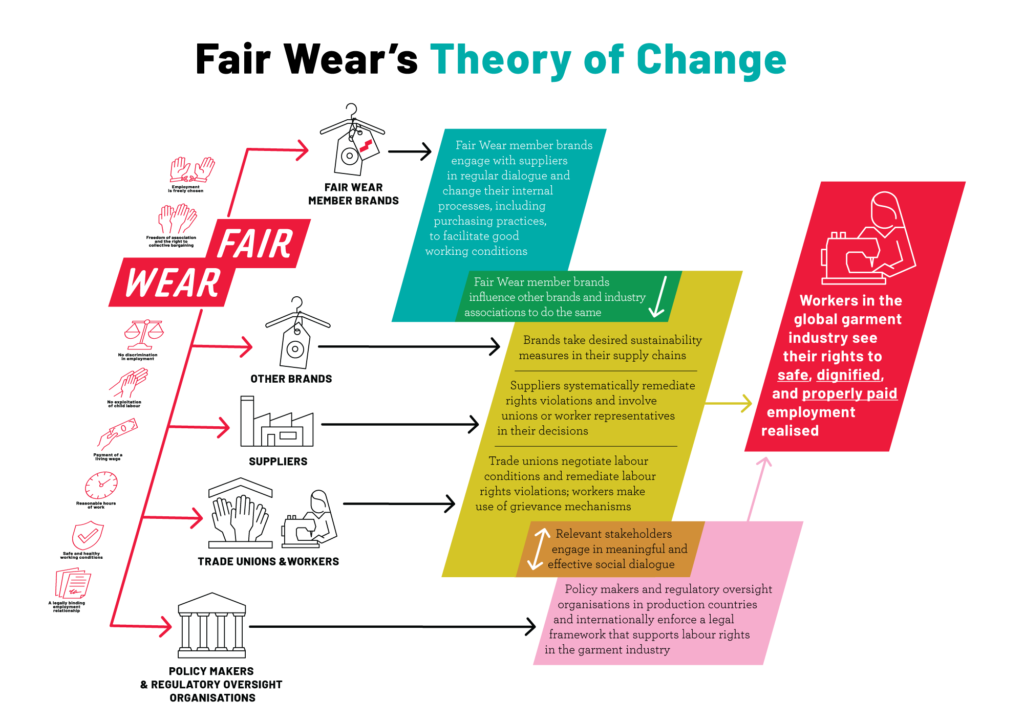

A Theory of Change (ToC) is a comprehensive roadmap.

It articulates how and why a desired change will occur in a particular context.

Unlike other planning frameworks, the ToC works backward from your ultimate goal.

This forces you to examine assumptions, identify necessary preconditions, and map the logical sequence of change.

The Center for Theory of Change defines it as “a specific and measurable description of a social change initiative that forms the basis for strategic planning, ongoing decision-making and evaluation.”

But this definition undersells its true power.

A well-developed Theory of Change forces honest conversations about what you believe to be true about change.

It explores why those beliefs are valid and what evidence would prove you wrong.

Key components of a Theory of Change include:

Long-term outcomes and impact: The fundamental change you seek to create.

This typically occurs over 5-10 years or longer.

Backward mapping: Start from your desired impact and work backward.

Identify necessary preconditions and earlier outcomes.

Assumptions: The underlying beliefs about how change happens.

If proven false, these would invalidate your approach.

External factors: Conditions beyond your control that influence whether change occurs.

Stakeholder perspectives: How different groups experience and contribute to the change process.

The Theory of Change emerged from evaluation practice in the 1990s.

It was developed by Carol Weiss and others who recognized that traditional evaluation missed the complexity of how social change actually happens.

Today, it’s become the gold standard for strategic planning in international development.

Organizations like the Ford Foundation require grantees to develop comprehensive Theories of Change.

Decoding the Logic Model: Linear Logic for Program Planning

The Logic Model offers a straightforward, linear framework.

It maps the logical relationship between your resources and desired results.

Developed in the 1970s for program evaluation, the Logic Model has become ubiquitous in nonprofit management.

Most government funders require it and it’s widely used for grant applications.

The W.K. Kellogg Foundation popularized the Logic Model through its widely-used guide.

They describe it as “a picture of how your organization does its work—the theory and assumptions underlying the program.”

The model flows logically from left to right: Inputs → Activities → Outputs → Outcomes → Impact.

Inputs: The resources you invest.

This includes staff, funding, materials, and partnerships.

Activities: What your organization does with those resources.

These are the services, events, and products you create.

Outputs: The direct, measurable products of your activities.

Examples include number of people served, workshops conducted, materials distributed.

Outcomes: The changes that result from your activities.

These are typically categorized as short-term (knowledge/attitude changes), medium-term (behavior changes), and long-term (condition changes).

Impact: The broader, systems-level changes that occur over time.

The Logic Model’s strength lies in its simplicity and universal applicability.

Whether you’re running a literacy program or a policy advocacy campaign, the basic logic holds.

Resources enable activities that produce measurable outputs leading to change.

This linear clarity makes Logic Models particularly useful for program management, staff orientation, and funder communication.

Theory of Change vs Logic Model: key differences

The Theory of Change starts with your ultimate impact and works backward, embracing the complexity and non-linear nature of social change while explicitly examining assumptions and centering diverse stakeholder perspectives.

This makes it ideal for complex, systems-level initiatives but requires significant time investment—often weeks to months for full development.

In contrast, the Logic Model begins with available resources and maps forward through a simplified, linear progression that focuses on the organization’s perspective while keeping assumptions implicit.

This approach offers clarity and quick development (days to weeks) that works well for direct service programs and traditional evaluation, but may miss the nuanced realities of how change actually occurs.

While government funders typically prefer Logic Models for their straightforward accountability, private foundations increasingly favor Theories of Change for their sophisticated analysis of complex social problems.

Case Study: Community Learning Partners Navigates Both Frameworks

Note: This is a fictional but realistic case study created to illustrate how these frameworks work in practice.

To understand how these frameworks work in practice, let’s follow Maria Rodriguez and Community Learning Partners (CLP).

They implement both tools as they navigate strategic planning.

CLP operates an after-school program serving 200 middle school students in East Oakland.

The program focuses on academic support and college readiness for first-generation immigrant families.

The Challenge

After three years of operation, CLP could demonstrate strong outputs.

They had 85% attendance rates, served 200 students annually, and conducted 40 parent workshops.

However, longer-term outcomes remained elusive.

Only 60% of students showed academic improvement.

Parent engagement varied dramatically.

High school counselors reported that CLP graduates weren’t significantly better prepared than their peers.

Maria suspected the issue wasn’t poor programming but unclear strategy.

CLP was doing good work without understanding why that work should lead to their stated goal of “breaking cycles of educational inequality.”

They needed strategic clarity.

But which framework would serve them best?

Building the Logic Model

Maria decided to start with a Logic Model.

She gathered her team of five staff members for a half-day retreat.

The process felt familiar—most had completed Logic Models for grant applications.

They quickly mapped CLP’s current approach:

Inputs: $300,000 annual budget, 5 full-time staff, school partnerships, volunteer tutors, curriculum materials.

Activities: Daily homework support, academic enrichment classes, parent workshops, college visit trips, summer programming.

Outputs: 200 students served, 1,000 hours of tutoring provided, 40 parent workshops, 85% attendance rate.

Short-term Outcomes: Students complete homework, improve study skills, increase academic confidence.

Parents understand US education system, connect with school staff.

Medium-term Outcomes: Students improve grades, develop college aspirations.

Parents support academic goals, advocate for their children.

Long-term Outcomes: Students graduate high school, enroll in college at higher rates than peers.

Impact: Educational inequality decreases in the community.

The exercise took four hours and produced a clean, logical progression that satisfied everyone in the room.

The Logic Model clearly showed how CLP’s resources produced activities that should logically lead to educational improvement.

Visual: CLP’s completed Logic Model showing all components

The Logic Model’s Limitations Emerge

However, when Maria presented the Logic Model to the board, uncomfortable questions emerged:

“Why do we assume homework support leads to college enrollment?” asked Dr. Patricia Kim, a board member and local high school principal.

“Some of our highest-achieving students never needed homework help.”

“What about the families who don’t attend parent workshops?” questioned Roberto Mendez, a parent representative.

“My neighbor’s daughter is succeeding academically, but her parents work two jobs and can’t attend evening sessions.”

The Logic Model, while logical, couldn’t address these complexities.

It assumed linear progression without examining whether those assumptions held true for CLP’s specific context and community.

Developing the Theory of Change

Recognizing these limitations, Maria decided to invest in developing a comprehensive Theory of Change.

She hired Elena Santos, an evaluation consultant, to facilitate a three-month process.

This involved staff, parents, students, and community partners.

The process began with outcome mapping.

They started from CLP’s ultimate vision: “East Oakland students from immigrant families achieve educational success at rates equal to their more privileged peers.”

Working backward, the team identified what would need to be true for this to happen:

Long-term Outcome (7-10 years): East Oakland immigrant students graduate high school and enroll in post-secondary education at rates comparable to district averages.

Intermediate Outcomes (3-5 years):

Students develop strong academic identity and believe college is achievable

Parents understand and can navigate US education systems effectively

Students possess academic skills and social capital necessary for high school success

Community institutions (schools, nonprofits, businesses) actively support student success

Short-term Outcomes (1-2 years):

Students complete assignments consistently and seek help when needed

Students develop relationships with adult mentors beyond family

Parents understand high school and college requirements

Parents develop relationships with school staff and other parents

Students participate in activities that build leadership and confidence

The Theory of Change process revealed crucial assumptions that the Logic Model had hidden:

Assumption 1: Academic support alone is insufficient.

Students need to see themselves as capable learners.

Assumption 2: Parent engagement requires more than information.

Parents need to feel welcomed and valued by schools.

Assumption 3: Individual student success requires community-level changes.

Institutions must better serve immigrant families.

Assumption 4: Success looks different for different families.

It should be defined by community members, not just academic metrics.

The process also identified external factors crucial to success.

These included immigration policy stability, school district leadership continuity, local economic conditions, and availability of affordable housing.

Visual: CLP’s Theory of Change showing branching pathways and interconnected outcomes

Stakeholder Perspectives Reshape Strategy

Most importantly, the Theory of Change process surfaced different stakeholder perspectives.

These fundamentally reshaped CLP’s approach:

Students valued peer relationships and wanted programming that felt relevant to their lives, not just academically focused.

Parents wanted to support their children but felt intimidated by schools.

They were uncertain about US educational expectations.

Teachers appreciated CLP’s academic support but wished the program better connected to classroom learning.

Community members wanted CLP to address broader issues like college affordability and immigration concerns affecting educational choices.

These insights led to significant program modifications.

CLP added peer mentorship components and redesigned parent workshops to be more collaborative and less instructional.

They created stronger partnerships with school-day teachers and began advocacy work around immigrant student rights.

Implementation and Results

Eighteen months after implementing changes guided by the Theory of Change, CLP’s outcomes improved significantly:

78% of students showed academic improvement (up from 60%)

Parent workshop attendance increased to 85% with much higher satisfaction rates

High school counselors reported CLP graduates demonstrated stronger self-advocacy skills

Three local schools requested partnerships to replicate CLP’s family engagement model

The Theory of Change provided flexibility to adapt programming based on what was working while maintaining focus on long-term goals.

When immigration raids increased community anxiety, CLP quickly added know-your-rights workshops without losing sight of educational objectives.

Strengths and Limitations: Choosing Your Tool

Theory of Change Strengths

Systems thinking: The ToC excels at mapping complex relationships between different factors influencing change.

For CLP, this meant recognizing that student success required changes at individual, family, school, and community levels simultaneously.

Assumption testing: By explicitly identifying assumptions, the ToC creates opportunities for learning and adaptation.

CLP discovered that their assumption about parent workshops was partially wrong—parents valued peer connections more than expert presentations.

Stakeholder inclusion: The ToC process centers different perspectives, often revealing blind spots in organizational thinking.

CLP learned that students wanted peer support as much as academic help.

Adaptive management: The ToC’s emphasis on learning enables mid-course corrections without losing strategic focus.

Theory of Change Limitations

Time intensive: Developing a comprehensive ToC requires significant investment.

CLP spent three months and $15,000 on facilitation—resources many organizations lack.

Complexity can overwhelm: The rich detail of a ToC can make decision-making more difficult.

CLP’s initial Theory of Change diagram was so complex that staff struggled to explain it to new volunteers.

Hard to standardize: Each ToC is contextually specific.

This makes it difficult to replicate or compare across organizations.

Evaluation challenges: The ToC’s emphasis on emergent outcomes can make traditional evaluation approaches inadequate.

Logic Model Strengths

Clarity and simplicity: The Logic Model’s linear progression makes it easy to understand and communicate.

CLP’s board immediately grasped the Logic Model during their first presentation.

Resource planning: The Logic Model excels at connecting resources to activities.

This makes it valuable for budgeting and operational planning.

Universal applicability: The same basic framework works across different program types and sectors.

Evaluation friendly: The Logic Model’s clear outcome sequence aligns well with traditional evaluation approaches that funders understand.

Quick development: Organizations can develop basic Logic Models in days rather than months.

Logic Model Limitations

Linear thinking: The Logic Model can obscure the complexity of how change actually happens.

CLP’s original Logic Model missed crucial feedback loops and external influences.

Hidden assumptions: The Logic Model’s simplicity can hide important assumptions about how change happens.

Organization-centric: The Logic Model typically reflects the organization’s perspective rather than centering community voices.

Limited adaptation: The Logic Model’s static nature can discourage learning and adaptation during implementation.

When Theory of Change and Logic Models Work Together

Rather than viewing these frameworks as competing alternatives, many organizations find value in using both tools strategically.

The Theory of Change provides strategic direction and systems understanding.

The Logic Model offers operational clarity and communication efficiency.

CLP now uses both frameworks in complementary ways:

Strategic planning: The Theory of Change guides long-term strategy development, program design, and partnership decisions.

Operational management: Logic Models help with staff orientation, volunteer training, and day-to-day program management.

Funder communication: CLP uses simplified Logic Models for government grants and comprehensive Theories of Change for foundation proposals.

Evaluation design: The Theory of Change informs evaluation questions and methodology.

Logic Models guide data collection and reporting.

This integrated approach allows CLP to maintain strategic sophistication while preserving operational clarity.

Practical Resources

For Theory of Change Development:

Theory of Change Guide by United Nations Development Group

Six theory of change pitfalls to avoid by SSIR

IPA’s Theory of Change Guide

For Logic Model Creation:

W.K. Kellogg Foundation Logic Model Development Guide remains the gold standard

Logic model workbook by Innovation Network

University of Wisconsin Extension provides excellent templates and examples

Final Reflections: Strategy as Living Practice

The choice between Theory of Change and Logic Model isn’t really about selecting the “right” tool.

It’s about matching your strategic needs with appropriate frameworks.

Organizations tackling complex, systems-level change benefit from the Theory of Change’s sophisticated analysis.

Those implementing direct services may find Logic Models perfectly adequate.

More importantly, both frameworks should be treated as living documents that evolve with learning and changing conditions.

CLP updates their Theory of Change annually and revises Logic Models quarterly based on program data and community feedback.

The most successful organizations recognize that strategic clarity isn’t a destination but an ongoing practice.

Whether you choose Theory of Change, Logic Model, or both, the real value lies not in the perfect diagram.

It lies in the conversations, assumptions testing, and stakeholder engagement that these frameworks facilitate.

As Maria Rodriguez reflects on CLP’s journey: “The Theory of Change didn’t just help us plan better programs—it helped us become better listeners, better learners, and ultimately, better partners to our community.”

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How long should it take to develop a Theory of Change versus a Logic Model?

A: Logic Models can typically be developed in 1-2 day retreats.

Comprehensive Theories of Change require 2-3 months with stakeholder engagement.

However, many organizations develop “light” Theories of Change in 2-3 weeks that capture the essential elements without extensive community consultation.

Q: Can small organizations with limited resources benefit from Theory of Change?

A: Absolutely.

While comprehensive ToC development requires investment, smaller organizations can adapt the backward-mapping approach and assumption identification without extensive facilitation.

Start with your desired impact and work backward.

Explicitly discuss what you believe needs to be true for change to happen.

Q: Do funders prefer Theory of Change or Logic Model?

A: It depends on the funder.

Government funders typically expect Logic Models.

Private foundations increasingly request Theories of Change.

Check funder guidelines.

Having both frameworks available allows you to match funder preferences while maintaining internal strategic clarity.

Q: How often should we update our Theory of Change or Logic Model?

A: Logic Models should be reviewed quarterly and updated as programming changes.

Theories of Change benefit from annual review with more substantial revisions every 2-3 years.

Update when significant external changes affect your context.

Q: What’s the biggest mistake organizations make with these frameworks?

A: Treating them as one-time planning exercises rather than living documents.

The real value comes from regularly revisiting assumptions, testing beliefs against evidence, and adapting strategy based on learning.

Both frameworks should inform ongoing decision-making, not just sit in filing cabinets after completion.